EXPERIMENT WITHIN THE HORIZON OF TRADITION

Radu Teaca most definitely is at the top of his own projected career. And from this high point, Radu puts forth his own personal alternative for the patriarchal cathedral already being built: an old looking building that’s not necessarily traditional, the exact opposite of how it should be.

I got to know Radu Teaca better in the early nineties, through our common mentor, professor Cezar Radu; we were both teaching at the time (I, a tad younger, was a tutor); he was working on an Orthodox cathedral project for the town of Oradea. He hadn’t yet emerged from underneath his workshop professor’s (Zoltan Takacs) umbrella, and this as well as Mario Botta’s or Richard Meier’s in”uences were coming through. Besides the ensemble’s elegance and harmoniousness, there were some theologically arguable issues present, like the separation of the sanctuary from the church’s main building, to which it remained connected only by a sketched altarpiece. Meanwhile, Radu became the outstanding architect he is nowadays.

The annual and biennial awards, the Arhitext Design prizes – he was getting them one after another; there were in fact years when he even got two of them for the same project. Ever since I included him in my “Zece arhitecti de zece” (“Ten grade A architects”, Bucharest: Noi Media Print, 2003) I was certain there was no way a list of top ten Romanian architects could be compiled without Radu Teaca being one of them. What is, however, much more important is that Radu is still at the very top of his field, getting, much like old wine, better and better with age.

THE CATHEDRAL

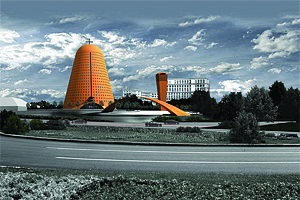

Perhaps because of the trend of traditionalism lacking tradition, Radu Teacă set himself against the grain by submitting to us a place of worship, without a doubt, but one we could hardly identify, visually, as pertaining to the Orthodox Christian imagery. It is, beyond any doubt, an architectural ensemble intelligently placed on that setting, with just a few simple objects standing out: a gate (triumphal arch) / bridge, a belfry / lighthouse and an enormous urban bell (a conical frustum completed by a dome) placed directly on the ground, like a Buddhist stupa.

Bud that’s just the outer shell. Inside, a second skin, tattooed with icons and light, describes a perfectly Orthodox interior, in which the prevailing direction is that of the mythical East, leading straight up, towards Christ Pantocrator. This predominance of the vertical brings to mind the Byzantine centred spaces, as well as our Walachian steeples, so unparalleled in the Orthodox space, as if the Greek churches received a vertical stretch on the dome’s axis.

Let one thing be well understood – the reason is not solely religious, it is also an urban profile one: the massiveness of the Palace of the Parliament can only be counterbalanced by such a slender vertical piece. Radu experiments, as we’re taught we should by Christian tradition. There is a need for, to use one of Andrei Pleșu’s phrases, experimenting within the horizon of tradition in religious architecture, in the Orthodox one in particular. We are still a few who, like Radu, believe there is a constantly growing need for this kind of experimenting. But, I fear, not enough to make up a critical mass. What Radu, however, is trying to tell us through these projects of his, which I have tried to place in the genealogy of his past works, is that he has at least tried.