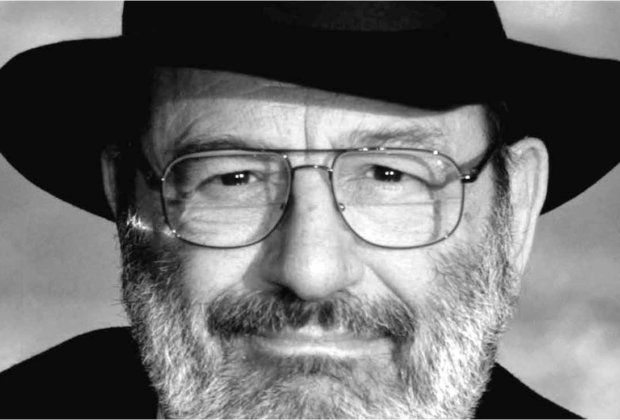

Umberto Eco – Today a country belongs to the person who controls communications

Philosopher. Novelist. Semiotician. Essayist. Literary critic. Professor. Journalist. Atheist. Known all around, however, still remaining a mysterious character, like many of those he wrote about. His first novel, The Name of the Rose (1980), sold over 50 million copies worldwide and made him famous, but not less enigmatic.

Although not counted among the six Italian laureates of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Umberto Eco is undoutedly one of the first 3-5 best known cultural personalities of Italy in the past century. The fact that millions of people read his novels and articles, while thousands of students use his scientific studies adds fame to his personality, yet it does not describe it.

“But now I have come to believe that the whole world is an enigma, a harmless enigma that is made terrible by our own mad attempt to interpret it as though it had an underlying truth”, Eco writes in his book Focault’s Pendulum (1988). Therefore, it is pointless to try explaining what makes his scientific works as interesting as his novels, and the latter as full of rich intellectual, cultural and historical references as a doctoral thesis, but without suffocating the thrilling plot.

On the other hand, it’s worth trying to answer another shorter question: who is he? And, if we were to take his word, expressed often until some years ago (when he was still open to giving interviews), everything happened “by accident.”

He had never dreamed of becoming a writer. “I consider myself a university professor who writes novels on Sundays,” he once declared. Letting his modesty aside, this is no exaggeration. Eco was a well-known journalist in Italy, having appeared both in top dailies and cultural periodicals, and a respectable academic, but he published his initial novel no sooner than at the age of 48. From the 1980s, he steadily became a global personality, thanks to The Name of the Rose being adapted for the big screen in 1986 and his prolific contribution to prestigious publications with international audience such as The New York Times.

Devoid of any interest in wealth and fame, everything he would achieve in life started with an insatiable thirst for knowledge and love for books. Against the urge of his father, who wanted to see his son become a lawyer, Umberto earned a degree in Philosophy in 1954. Ironically, while preparing his thesis on Thomas Aquinas – a defender of faith, regarded as the greatest Catholic theologian – he renounced believing in God and severed his ties to the Roman Catholic Church.

From that moment onwards, the future world famous writer began searching for meanings in the relativistic contemporary world, by questioning long established norms and beliefs and by proposing new interpretations. In an age (the 1960s) of sociopolitical and cultural upheavals, he didn’t take sides with political reformists, utopists and revolutionaries. He chose the realms of literature, art, and mass culture as his field of battle.

A different outlook on literature

Self-described “lover of the smell of book ink in the morning,” a passionate bibliophile, owning around 50,000 volumes (including some 1,200 rare original editions) in his apartment in Milan and his holiday house in Urbino, Eco proposed a new paradigm of weighting the value of literary texts. In his 1962 book Opera aperta (The Open Work), he argues that literature which limits one reader’s potential understanding to a unequivocal perspective is a ‘closed text.’ Such a work, no matter how well-written, is due to remain less rewarding for the reader, while an ‘open text’ is one that allows various interpretations, in different contexts.

Readers are incited to search for meanings and thus the reading experience is more rewarding. This means that, according to Eco’s view shared with The Paris Review (2008), “a good book is more intelligent that its author. It can say things that the writer is not aware of.” The Italian scholar, founder of the Institute of Communications Disciplines at Europe’s oldest universtity (Università di Bologna, founded in 1088), questions not only literature which is too linear, propagandistic, but culture as a whole and especially the relation between politics and mass culture in our times. Both as a professor and writer, he challenges his audience to look for deeper meanings, more or less concealed by the apparent connotation of words.

In his book Faith in Fakes (1986, republished as Travels in Hyperreality in 1995), Eco describes how the contemporary public is subjected to mystification and manipulation and advises all of us to have an attitude of ‘diffidenza’ (healthy suspicion). As an academic and journalist, he has been waging a ceaseless ‘semiological guerrilla’ against the media and the political power.

“Not long ago, if you wanted to seize political power in a Country, you had merely to control the army and the police. Today it is only in the most backward countries that fascist generals, in carrying out a coup d’etat, still use tanks. If a Country has reached a high level of industrialization the whole scene changes. Today a country belongs to the person who controls communications,” Eco foretold in a study published in 1973 (Towards a Semiological Guerrilla Warfare), long before many ‘revolutions‘ around the world took place under TV and social media orchestration.

Confessing that he regularly watches television, Umberto Eco warns us that “A democratic civilization will save itself only if it makes the language of the image into a stimulus for critical reflection – not an invitation for hypnosis” (Can Television Teach?, 1979).

Faithful in the immortality of books

Umberto Eco is a skeptic, believing that religion and God are inventions of humans looking for meanings, but not a militant atheist. He has has never taken on a role of giving publicc speeches against religion. Though being one of Italy’s most famous atheists, at least three of his over 30 honorary degrees were granted to him by Catholic universities.

While his spirit prevents him from adhering to a revealed Truth, he is at ease in the universe of books which “are not made to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry.

When we consider a book, we mustn’t ask ourselves what it says but what it means…” (The Name of the Rose). “We live for books. A sweet mission in this world dominated by disorder and decay,” a character in the same novel says.

Eco believes that “To survive, you must tell stories” (The Island of the Day Before, 1994), but makes no distinction between fiction and forgery, according to a surprising confession that his huge libraries are made up of “books whose contents I don’t believe,” made in the conversation-book This is Not the End of the Book (co-authored with screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière in 2012). Moreover, he declares himself “fascinated with error, bad faith and idiocy.”

Unlike many scholars in the early 1960s, he didn’t dismiss the James Bond character, nor Superman comics as ‘junk fiction.’ As he has done since early childhood, he still reads a lot and likes a lot of what he reads; his interests range from curiosity about why people tell lies to human fascination with fakes, forgery, conspiracies, mystery, failed scientific research, occultism and so on.

Also, against the gloomy view that books are doomed to disappear, Eco notices how new media have left the world scene as quickly as they entered it, citing floppy disks, videotapes and CD-ROMs. In the meantime, books proved to be more durable, he dares to make another prophecy: “We can still read a text printed five centuries ago. The book is like the wheel. Once invented it cannot be bettered.”